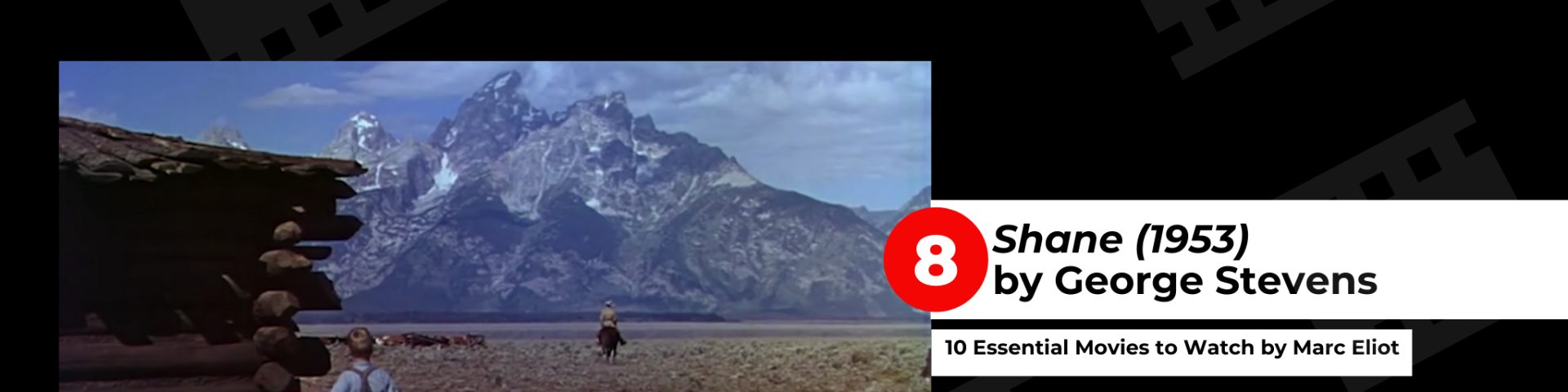

10 Essential Movies to Watch by Marc Eliot 8. Shane, by George Stevens (1953)

I’ve always been a big fan of Hollywood westerns. The first and, I think, primal realization about film is that if one wants to learn history, one should read a history book. While not historically accurate, there is a cinematic truth inherent in Hollywood’s revisionist version of the old west.

8. Shane, directed by George Stevens (1953)

That truth is contained in the horizons that director John Ford fell so in love with in Monument Valley, and that he used to measure and framed America as he perceived it; that truth is visible by minority players in studio-era films made to convey a message of their own manufactured inferiority; that truth is how physical beauty, both male and female, holds a redemptive power so mysterious, transcendent and mesmerizing audiences for a century have been happily manipulated by it without ever wondering why; that truth lies in the unquestioning patriotism of Hollywood westerns and their at times insanely illogical, relentlessly happy endings.

Hollywood’s message in all genres has always been that no matter how bleak the situation, everything will turn out all right by the closing credits. This credo resonates historically as well; it helped America survive through the Great Depression, World Wars 1 and 2, and beyond. Shane has one of the most basic plot lines of westerns (when “Indians” aren’t involved – there are no “Indians” in the film save one sitting outside the general store), the struggle over land and water rights.

In the developing west, older settlers wanted to keep the land they took from the “Indians” for their cattle to graze, some of which was now being granted by the government to easterners and, worse, immigrants, to encourage homesteading and fulfill the nation’s Manifest Destiny. Here, then, the oldest conflict in America – the poor looking to move up Vs. the wealthy who want to keep them down.

In Shane, the homesteaders are, with one or two exceptions, immigrants, an important element of the story and one that continues to resonate to this day. One of the new settlers, not an immigrant (they can’t possibly do anything without real Americans leading them in Hollywood’s version of history) organizes the others to stand up to the cattle barons.

Into the mix rides Shane, a mysterious figure who is a living anachronism – a gunfighter who long ago helped settle the land with his gun rather than his butter, only to find it churning with unrest once more. He wants to put his violent past behind him but, in the end, can’t escape it. As Heraclitus wisely said, one’s character determines one’s fate, and so, with no future, wounded and out of time, Shane (quite eloquently) rides up to Boot Hill to die, a man out of time. As he does so, the son of a settler he helped calls after him – “Shane, come back” (one of the most memorable lines in all of Hollywood cinema).But, for Shane, there can be no turning back.

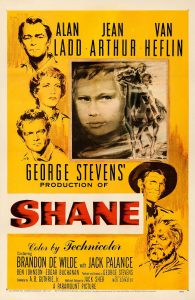

The themes in Shane are grand without being grandiose. As played by Alan Ladd, Shane is the ultimate reluctant hero of American movies, the speak- softly-carry-a- big-stick character that doesn’t look for a fight but never shies away from one. Fear does not exist in Hollywood heroes.

Complex subplots abound – the little boy may, in fact, be Shane’s, from another part of his mysterious past. It might be no accident, after all, that this aging gunfighter wandered onto this property and became involved in their battle for survival, ultimately giving up his life so the boy will have a future.

Shane was shot in color and wide-screen 70 mm (1:66 ratio), with brilliant stereophonic sound that enhanced the blast of gun shots. The film marks the highlight of Alan Ladd’s career (Shane), Brandon De Wilde’s debut as the boy (I knew him, he grew up in NYC, and sadly died very young in an automobile accident); Jean Arthur, in what was the final screen role of her illustrious career; studio veteran Van Heflin as her husband, who organizes the others; Jack Palance in his first major appearance onscreen, a terrifying one at that.

Shane ends as all films do, with a resolution, or what I call the real or metaphoric shoot-out. In this instance, both. It is a completely beautiful film, stylistically and thematically.

It was shot the same time as Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (the productions were next to each other; Zinnemann borrowed a crane from George Stevens for the great overhead pull-back that showed the deserted town in his film) but Paramount had to delay Shane’s for a year because of the outsize success of High Noon.

Shane represents the best of the industry’s at times uncanny ability to chronicle its own slow and agonizing demise. Both Shane and Shane are relics of the past, living on borrowed time. Shane, of course, is Hollywood.

Easily available, should not be missed.

Read the past recommendations and more content from Marc Eliot at the UFM Film School:

- Teaching an Auteurist Approach to Cinema for Film Students at the UFM Film School

- Artista Emprendedor: The Business of Hollywood con Marc Eliot