Marc Eliot’s Top 10 Classic Movies for Film Students to Watch

Hollywood biographer and UFM Film School visiting professor Marc Eliot shares his top 10 recommended classic movies for aspiring filmmakers:

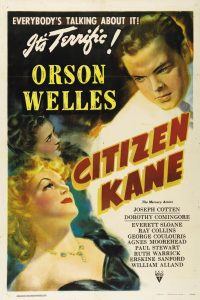

1. Citizen Kane (1941), director: Orson Welles

It doesn’t matter how many times one sees this film, it is the ultimate cinematic experience and the best Russian puzzle doll; each time you think you’ve found the smallest, subtlest detail, another one is revealed. This is the picture that introduced Hollywood to the world of modern filmmaking. I could teach an entire course just on this one film, looking at a different aspect each week (themes, cinematography, sound, acting, script writing and structure, set design, and on.

To begin with (and only to begin with), Welles’ use of deep-focus to illustrate an ambiguous mise-en-sense doesn’t just illuminate the film’s theme (of ambiguity, Kane’s inability to make a choice, for one, and stick to it, or where his true emotions lie), ambiguity is the theme of the picture. Welles, nor anyone else, ever matched this magnificent feat. Mandatory for any and every film student.

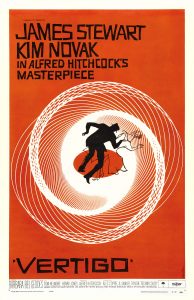

2. Vertigo (1958), director: Alfred Hitchcock

No other filmmaker in Hollywood ever dared to approach the subject of fetishism to the degree that Hitchcock does in this film. Trying to bring a dead woman back to life by recreating her in another woman is not only the ultimate fetishistic denial of death, but a fantasy that everyone shares in one way or another (a lost girlfriend/boyfriend, a dead parent, a younger version of a wife/husband, it never ends).

Moreover, Hitchcock uses the locale of San Francisco as a visual metaphor for the emotional hills and valleys of schizophrenia – the ups and downs of the long sequences where Jimmy Stewart in his car follows Kim Novak in hers around the city remain among the most accessible demonstrations of film-as-metaphor. Finally, the subplots pile upon themselves as the many-layered double-crosses serve as a flattened mirror-image of the desire of one lost soul to turn another — into an object of desire! A must-see for all who love film.

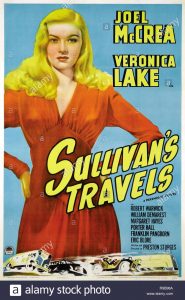

3. Sullivans Travels (1941), director: Preston Sturges

Sturges made the funniest and most important comedy of Hollywood’s sound era. A class-conscious film that combines slapstick, satire, mixed into a bitter commentary of Hollywood’s never-ending need to turn away from reality, makes this one of the finest films to ever come out of the studio system. The film mocks the very medium it was made in – cinema – to create an effective work of film. Cannot recommend it highly enough. Be prepared to laugh out loud.

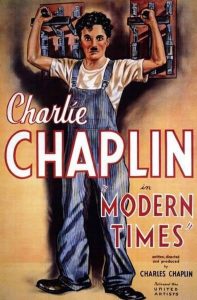

4. Modern Times (1936), director: Charlie Chaplin

Possibly Chaplin’s, and therefore, Hollywood’s greatest achievement. This is the film that defines what pure cinema is; the reality of Chaplin’s character is not in what he sees, but in what we see he sees. The final shot, of his face, not of the girl’s, is one of the most poignant and revelatory in all of cinema. Remarkably, this is, for all intents and purposes, a silent film, even though it was shot a full decade after sound began appearing in motion pictures. Hilarious, wise, and endlessly entertaining, it is the most precious gem of 20th Century filmmaking.

5. Shoot the Piano Player, 1960, director: François Truffaut

5. Shoot the Piano Player, 1960, director: François Truffaut

This French film is one of the most perfect examples of the post-war “nouvelle vague.” The term is often mistakenly translated into English as “New Vague,” but the correct translation is “New Wave.” The film is, of course, anything but vague, a tidal wave of personal cinema. The French reintroduced, to the bloated and dying Hollywood industrial studio era, the notion that film could be a personal, rather than a social, instrument of communication.

Truffaut reimagines himself as a failed concert pianist playing in small bars who invariably gets caught up in a series of fatal events over which he has no control. It is, therefore, a metaphor for the systems of filmmaking, both in France and the United States that tried to squelch Truffaut’s personal vision. It was held up from distribution in the States for years for the little bit of nudity in one or two scenes, which reveals far more about America than it does about France. Charles Aznavour, the celebrated French cabaret singer who passed last year, plays Truffaut’s “other,” and resembles him physically to a remarkable degree. There is, simply, no other film like it.

6. Contempt, (1964), director: Jean-Luc Godard

Things had changed so much in the time between “Shoot the Piano Player” and “Contempt,” that in order to get distribution in the States, the film had to add footage of a nude Brigitte Bardot. Perhaps the most beautiful woman to ever appear on any screen in the world, this is, by far, her best film. The co-star, Michel Piccoli, a mainstay of French Cinema (he just died, two weeks ago), gives a bravura performance as well, especially in the extended and much-celebrated “argument” sequence between him and his frustrated wife (Bardot) in which Godard follows them both, via hand-held, in a scene that encapsulates the entire story of their marriage, and marriage in general.

With appearances by Fritz Lange and Jack Palance, shot on location in Greece, “Contempt” is a glorious example of personal yet big-screen, beautiful color French Cinema by one of its most talented, if eccentric, filmmakers. There is a reason, the French would say, why the first three letters of his last name are G-O-D.

7. The Searchers (1956), director: John Ford

One of the most majestic films ever made, starring John Wayne at his deepest, darkest, and most complex, directed by Ford as a family affair. Everyone in the film is related in real-life, even as the story centers on what the notion of family is. The story of prejudice in America has never been more fully and frankly shown on screen. George Lucas based his opening of the original “Star Wars” on the house-burning sequence in “The Searchers.” This is not just a western, it is the western, against which all others must be measured. One of the best lessons in filmmaking ever to be seen. Shot in 70mm.

8. The Scarlet Empress (1934), director: Joseph Von Sternberg

Dietrich at her most exotic, Sternberg at his most enslaved (by Dietrich). Here the story of the Russian empress is told as if from the pages of a Hollywood gossip magazine. Although the story takes place in the 18th century of empirical Russia, the climax is played out against Tchaikovsky’s 19th century “1812 Overture,” which, somehow, seems fitting. Rousing, sophisticated, sensual, and grotesque, this example of German Expressionism gone crazy is, in my opinion, the best work of the Dietrich/Von Sternberg tidal wave that left behind the rest of ‘30s Hollywood in its wake.

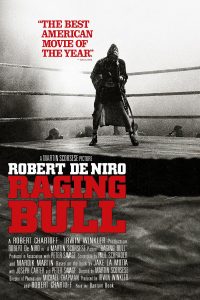

9. Raging Bull (1980), director: Martin Scorsese

9. Raging Bull (1980), director: Martin Scorsese

The best example of how the absence of morality is the best way to illustrate the importance of morality. A cautionary tale with a performance by Robert De Niro that is, simply, like nothing else ever filmed. A national treasure.

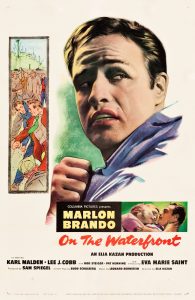

10. On The Waterfront (1954), director: Elia Kazan

There is so much to say about this film, there is not nearly enough space here to even begin to do it justice.

It made Marlon Brando’s film reputation (and won him his first Oscar); the film defined the evils of Blacklist and the HUAC purge of Hollywood like no other; it is the finest depiction of the Method Acting craze of the ‘50s – virtually everybody in the film – Brando, Eva Marie Saint, Lee J. Cobb, and Rod Steiger – were all Actors Studio alumni and Elia Kazan had created the Group Theater; the script, by former sports writer Budd Schulberg, is Shakespearean, especially in its use of specialized language and speaking rhythms; the climactic confrontation between the corrupt union boss and the enlightened dock worker is not to be missed – audiences never fail to cheer; the beautiful score is by no less than Leonard Bernstein.

All combined to make this one of the truest classics of the Hollywood era of filmmaking. Winner of eight Academy Awards, deservedly so, including Best Picture of the Year.

Do you want to study cinematography at UFM’s School of Film and Visual Media? Learn about the admission process!

More on Marc Eliot´s activities at the UFM Film School:

- Marc Eliot: Teaching an Auteurist Approach to Cinema for Film Students at the UFM Film School

- Artista Emprendedor: The Business of Hollywood con Marc Eliot