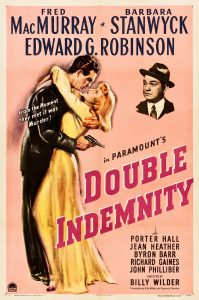

10 Essential Movies to Watch by Marc Eliot 5. Double Indemnity (1944) by Billy Wilder

5. Double Indemnity, directed by Billy Wilder. (1944).

This is the Hitchcock film that Hitchcock never made. If there is any flaw in the universal moral guilt Hitch presented to the world, it is that while he may have taken viewers to the edge and peered into the abyss of darkness and despair they deserved to fall into, he never let them, or his onscreen heroes, actually do so (Psycho being the only exception and, some say, the one true deserving-of-greatness Hitchcock film). With Double Indemnity, Wilder took us and his players to the edge, and then drop-kicked all of us into it, to that place from which there is no return.

Made in 1944, starring Barbara Stanwyck, in a role more familiar to audiences than the scammer she played in The Lady Eve (although, as it turns out, both are scammers), Phyllis (Stanwyck) is the ice-queen wife who devises a fiendish plan to murder her husband and make it look like an accident, to collect the double indemnity (twice the insured amount) on his life insurance policy.

To assist in her nefarious scheme, she seduces Walter, the glad-handing insurance salesman, played by the normally affable Fred MacMurray in what was, without question, the performance of his career. The film also stars Edward G. Robinson as the insurance company investigator, and Walter’s best friend, who, painfully, discovers the truth behind the murder that destroys everyone involved in it, including Walter.

Femme fatales are the spine of every Hollywood murder/suspense film, but few have ever been taken so far, or so fully realized as Phyllis Dietrichson, thanks to Stanwyck’s bravura performance, and the great script by Wilder and his co-writer, Raymond Chandler, adopted from the novel written by James Cain, (Chandler also wrote the screenplay for Hitchcock’s wondrous Strangers on a Train).

Anyone familiar with Chandler’s novels knows how they reach the high plateau of literature, and the few films he wrote for Hollywood, a medium for which he had great disdain, have dialogue, dizzying plots and dazzling twists like no others”.

The verbal backs-and-forths between MacMurray and Stanwyck astound, as does the great monologue by Robinson (who easily steals the film from both leads), one of the most famous scenes in film history, when he explains to his brainless boss why the victim (Stanwyck’s husband) couldn’t possibly have committed suicide (what the boss wants to get the company out of paying off).

All three – Stanwyck, MacMurray and Robinson should have been nominated for Academy Awards, but the film, nominated for seven, was shut out by Oscar. It lost Best Picture to Leo McCarey’s sappy Going My Way, a film with all the hollow uplift needed for audiences mostly of women whose husbands, fathers and sons were off fighting World War II.

All three – Stanwyck, MacMurray and Robinson should have been nominated for Academy Awards, but the film, nominated for seven, was shut out by Oscar. It lost Best Picture to Leo McCarey’s sappy Going My Way, a film with all the hollow uplift needed for audiences mostly of women whose husbands, fathers and sons were off fighting World War II.

Wilder also lost Best Director to McCarey. Stanwyck lost Best Actress to Ingrid Bergman in George Cukor’s Gaslight, and Wilder and Chandler lost out as screenwriters to Frank Butler and Frank Cavett for, yes, Going My Way. Eddie Robinson, who should have won Best Supporting Actor wasn’t even nominated, probably because he was not very popular in Hollywood for his pre-war left-wing activism that eventually led to his brief stint on the ‘50s Blacklist (rescued from it, incidentally, by Charlton Heston).

To younger audiences, Wilder is remembered mainly for his comedies, most impressively The Apartment that won Best Picture in 1960, starring Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine, but his decades-long list of achievements in film remains among the most impressive. Besides Double Indemnity, they include the 1951 classic, Sunset Boulevard for which he won two Oscars (Hollywood films about Hollywood is a wholly separate category we may get in to one day.

The studio-era film industry saw itself as a microcosm of the entire country, which it decidedly was not, thereby making its “autobiographical” films exercises in realistic-looking absurdism). Wilder is long overdue for an upward auteurist reevaluation. His ascent to the Pantheon begins with Double Indemnity, one of the most erotically suggestive films ever to slip under the radar of the industry’s strict code of censorship.

Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray (1944)

Here, on full display (along with Stanwyck’s ankle bracelet that plays a key role in the seduction), is the dark side of the war between the sexes (we look to Sturges for the bright side). In full reductio ad absurdum, Wilder illustrates, quite convincingly, what women will do to men to get their way, and what men will do for women to…well, you get the picture.

Get the picture, easily available.

We are halfway through with Marc Eliot’s top 10 series! Check out his past recommendations:

- 1. Stars by the Pound (2018) by Marie-Sophie Chambon

- 2. The Lady Eve (1941) by Preston Sturges

- 3. Fire Will Come (2019) by Oliver Laxe

- 4. A Face in the Crowd (1957) by Elia Kazan

Stay tuned for next week’s recommendation!