Alfred Hitchcock Redux By Marc Eliot | Saboteur (1942) and Notorious! (1946)

In this article, we will look at Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) and Notorious! (1946):

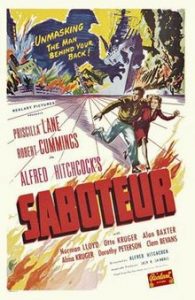

Saboteur (1942)

1. Saboteur (1942) is Hitchcock’s first fully-realized American film, free from the commercial ties that bound him to David O. Selznick. With the outbreak of the Second World War, the British Film Industry and its largest studio, Gaumont, had to all but shut down for the duration. Scores of British actors, writer, producers and directors came to Hollywood, among them David Niven, Ronald Coleman, Leslie Howard (who had already appeared in Gone with the Wind), Richard Todd, Alec Guinness, Dirk Bogarde, Denholm Elliott, and Audrey Hepburn; their British accents and mannerisms endeared them to American audiences who believed their affectations were superior to those of the likes of American aw-shucks stars Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, the always cocky Clark Gable, and so many others who’d never seen Paree. Instead of leaving the farm, they brought it with them to Hollywood. Their calculated hayseed naiveté and smart-aleck bravado was Hollywood’s way to balance the stiff upper-lip films from the other side of the pond.

In 1939, with the outbreak of the war in Europe, Hitchcock was brought to Hollywood by independent producer David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind). His first assignment was the gothic Rebecca (1940) that won Best Film of the year at the Oscars (the award goes to the producer, Selznick, not the director). Although the film was a hit, Hitchcock believed it was much more reflective of Selznick’s vision than it was his own. He was reluctant to continue to make movies for Selznick, and the producer felt the same way about Hitchcock. Neither liked the other’s methods; Hitchcock felt Selznick was over-stylized, Selznick thought Hitchcock too distant. Selznick then loaned Hitchcock out to various studios, collecting fees that weren’t shared with the director, who continued to earn his salary and no more.

In 1939, with the outbreak of the war in Europe, Hitchcock was brought to Hollywood by independent producer David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind). His first assignment was the gothic Rebecca (1940) that won Best Film of the year at the Oscars (the award goes to the producer, Selznick, not the director). Although the film was a hit, Hitchcock believed it was much more reflective of Selznick’s vision than it was his own. He was reluctant to continue to make movies for Selznick, and the producer felt the same way about Hitchcock. Neither liked the other’s methods; Hitchcock felt Selznick was over-stylized, Selznick thought Hitchcock too distant. Selznick then loaned Hitchcock out to various studios, collecting fees that weren’t shared with the director, who continued to earn his salary and no more.

Via the loan-out arrangement, Hitch made 1942’s Saboteur at Universal. By then, the war had reached America and studios were obligated by Washington to make patriotic films that kept up the morale of the mostly female ticket-buying audiences (husbands, fathers and brothers, and some sisters, were overseas).

Saboteur marks the first time Hitchcock introduced his Calvinist/Freudian themes of universal guilt and its consequences in a commercial Hollywood film. In it, his protagonists’ battles with their antagonists become their externalized, dramatized version of their struggle within, between good against evil.

In the film, Hitchcock, ever the visual architect, traverses the American map as Barry Kane (Robert Cummings), is working at a defense plant, conveniently stateside and civilian during the war.

Through a quickly laid-out plot, his best friend is killed by an “enemy” plant explosion and he becomes the prime suspect. This is one of Hitchcock’s favorite tropes, the innocent man drawn into an immoral conspiracy of which he is blamed – the good within challenged by the forces of evil. To save himself, and, by extension, the country, Kane sets out to find the real killer. Because this is a Hollywood movie, along the way he falls in love with pretty blond Priscilla Lane (best remembered for her performance opposite Cary Grant in Frank Capra’s 1944 Arsenic and Old Lace). To win her trust and affections, he has to convince her of his innocence, then enlists her to capture the real killer(s).

The film’s climax, at the top of the Statue of Liberty, remains one of the most famous in American cinema. As the evil Frye (Norman Lloyd) dangles from a ledge, literally by a thread, Kane risks his own life to save him and to clear his own name. Thus, good Vs. evil goes the distance to the final round. You’ll have to see the film to find out who prevails (as if you didn’t know).

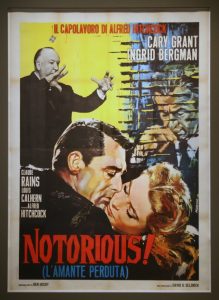

Notorious! (1946)

2. Notorious! (1946), produced and directed by Hitchcock, is set in Latin America during WWII, where (improbably) the FBI is tracking down a group of “enemies” (i.e. Nazis; in 1946, the year of the film’s release, the United States had already begun a major rebuilding plan for Western Europe, including Germany, as a way to defend these countries from being overtaken, willingly or otherwise, by the Soviet Union. Hence, Hollywood was advised to play down the use of the word Nazis to keep relations with post-war Germany firmly on the side of the west).

Starring the ever-suave, ultra-charismatic Cary Grant, one of Hitchcock’s idealized on-film others (Cummings, Jimmy Stewart and Grant were his favorites); Swedish-born Ingrid Bergman, prior to her banishment from Hollywood for carrying on an extra-marital affair with Italian director Robert Rossellini, whom she eventually married; the always wonderful (British) Claude Rains as Grant’s (Hitchcock’s) dark-side doppelganger.

Starring the ever-suave, ultra-charismatic Cary Grant, one of Hitchcock’s idealized on-film others (Cummings, Jimmy Stewart and Grant were his favorites); Swedish-born Ingrid Bergman, prior to her banishment from Hollywood for carrying on an extra-marital affair with Italian director Robert Rossellini, whom she eventually married; the always wonderful (British) Claude Rains as Grant’s (Hitchcock’s) dark-side doppelganger.

In Hitch’s words, “Notorious was simply the story of a man in love with a girl who, in the course of her official duties, had to go to bed with another man and even marry him.” Can there be any doubt as to why Hitchcock chose Bergman for this role? And, as always, the great director sought to simplify the themes of his films, to make them more attractive to audiences, when discussing them with journalists, in this case Francois Truffaut.

There is a huge Freudian influence in this film, as the Austrian-born founder of Psychoanalysis was very much in vogue for Hollywood scriptwriters. In the film, Grant (the FBI agent) competes with Rains (the enemy) for Bergman’s love (another FBI agent), and the closer she gets emotionally to Rains, for political purposes, the more she is convinced she will have to marry him, and the more desperate Grant becomes to prevent her from doing so. Moreover, Rains’ mother, played by Leopoldine Konstantin (in her final film role,) wants to kill Bergman, ostensibly for political reasons, but, on a deeper level, because she doesn’t want to share the love of her mama’s boy with another woman.

With a plot that makes no sense, involving radiated “particles,” spying and whatever else Hitchcock could throw into the thick soup of this story, looking beyond it reveals a more personal exploration of the conflict between good and evil, with the alleged protagonist, Grant, and the far more sympathetic (and pathetic) antagonist, Rains, two sides of the same person – the struggle within – personified by these great players.

The film is remembered today as one of the most sophisticated of Hitchcock’s prodigious career, including the famous bravura single shot that starts at the very top of a grand ballroom to a close-up of Bergman’s fingers hiding a key. Always, in Hitchcock, hands, tips of fingers, shoes, suits, lighters, wine bottles, paintings, take on lives of their own, objects with their own, often sinister personalities. In this film, the key serves just that purpose, along with a climactic winding staircase, the latter a familiar symbol in many of Hitchcock’s films, including Strangers on a Train, Vertigo, Rear Window, North by Northwest, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Saboteur to name a few. Hitchcock’s films often deal with heights, staircases, people holding on by their fingertips either to a ledge or each other, sometimes by a literal thread, as in Saboteur. Notorious is a rarely-seen forties Hitchcock gem that should not be missed, by students at the university and Hitchcock fans the world over, wherever and whomever they may be.

Read the first part of Marc Eliot’s Alfred Hitchcock Redux!

Next week: read the final part of Marc’s analysis on Hitchcock’s movies.

More content by Marc Eliot you might enjoy:

- Marc Eliot: Teaching The Art of Film for Students at the UFM Film School

- Marc Eliot’s Top 10 Classic Movies for Film Students to Watch

- Cine Foros UFM: Análisis cinematográficos de películas recomendadas por cineastas internacionales