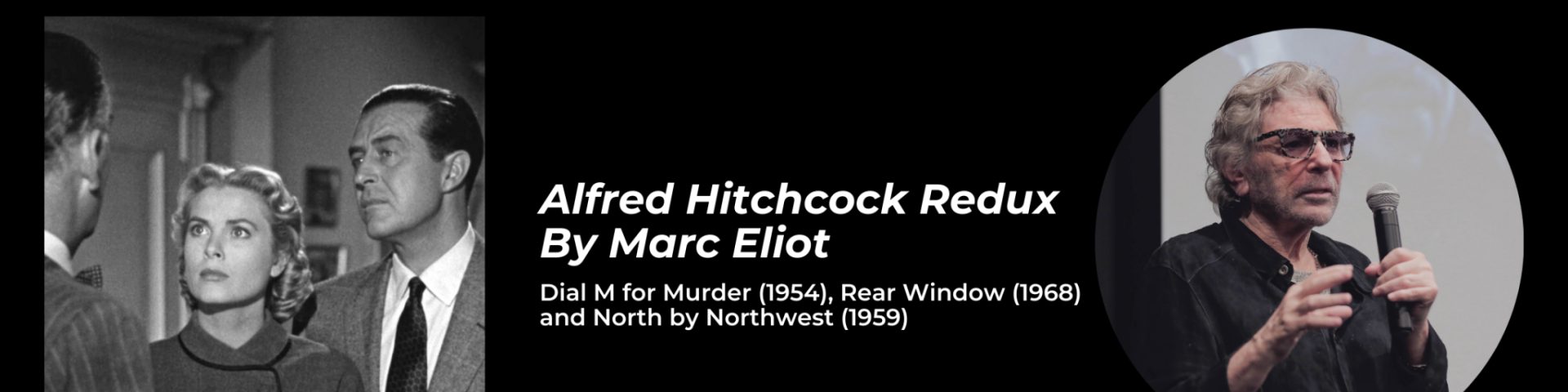

Alfred Hitchcock Redux By Marc Eliot | Dial M for Murder (1954), Rear Window (1968) and North by Northwest (1959)

Dial M for Murder (1954)

3. Dial M for Murder (1954). One of the less-regarded Hitchcock films of the fifties, Dial M has grown in stature since its release. In this British-set film (made in Hollywood for Warner Bros) Hitch again confronts the inner struggle between the forces of good and evil in his main characters, including the luminous Grace Kelly, one of his most favorite leading-lady blondes.

As Margot, Kelly has been carrying on an extra-marital affair that, through a series of convoluted entanglements, leads her to commit an unintended murder that leads her straight to the gallows before a last-ditch effort to save her life. Her husband, Tony, played by Ray Milland (another British export who’d previously won a Best Actor Oscar for his performance in Billy Wilder’s 1945 The Lost Weekend) is the scheming husband, charming on the outside, a viscous murderer within, who plans a way to have his wife killed by the State so he can inherit her money.

Robert Cummings returns as Mark Halliday, Margot’s illicit lover who has his own reasons for trying to save Margot. And the inimitable John Williams, he of the mustache-combing set of British stiff-upper- lippers, plays Inspector Hubbard, the God-like figure of justice who dispassionately unravels the tangled plot by discovering the “key” to Tony’s clever scheme.

Robert Cummings returns as Mark Halliday, Margot’s illicit lover who has his own reasons for trying to save Margot. And the inimitable John Williams, he of the mustache-combing set of British stiff-upper- lippers, plays Inspector Hubbard, the God-like figure of justice who dispassionately unravels the tangled plot by discovering the “key” to Tony’s clever scheme.

Originally shot in 3D, at Warner Bros insistence, by the time the film opened the fad had faded and it was almost universally seen in flat-screen. Although there is a 3D version available, it requires prohibitively expensive equipment to show it. Thoroughly enjoyable in 2D, this is an acting tour-de-force for Kelly, Cummings, Milland and Williams, seen through Hitchcock’s Calvinist-Freudian lens.

Rear Window (1968)

4. Rear Window (1968) –Arguably the best of all Hitchcock films, the master’s masterpiece, as it were, Rear Window is less oblique than Vertigo, less gothic than Psycho, less circumstantial than Strangers on a Train, less ambitious than North by Northwest and more accessible (and successful, artistically and commercially) than Marnie. Rear Window is Hitch’s most blatantly Oedipal exercise in the activities of the malevolent subconscious within even the most apparently innocent of men (here played by one of Hollywood’s iconic “good guys” James Stewart. Reaching a new level of comprehension regarding the secret desires that lurk between the innocent longings and the lustful wishes of having it both ways, in Rear Window the link between the physically compromised Stewart and the morally rotted Raymond Burr is forged by both men’s desire to free themselves from their (and Hitchcock’s) perceived chains of merciless matrimony.

In Freudian terms, “rear window” stands for the subconscious. From his wheelchair, Stewart gazes out at all the rear windows in his Greenwich Village apartment courtyard and watches, spies on really, all the anecdotal lives of his neighbors. Seen through their wide panes that resemble movie screens, all their stories share the common theme of marriage – the fear of, the wish for, the cheating in, and, finally, the desire to escape from a spouse. At its most profound, Stewart’s voyeuristic projection of his own fantasy – to murder Grace Kelly rather than marry her, is deepened by the audience’s voyeuristic of him.

In Freudian terms, “rear window” stands for the subconscious. From his wheelchair, Stewart gazes out at all the rear windows in his Greenwich Village apartment courtyard and watches, spies on really, all the anecdotal lives of his neighbors. Seen through their wide panes that resemble movie screens, all their stories share the common theme of marriage – the fear of, the wish for, the cheating in, and, finally, the desire to escape from a spouse. At its most profound, Stewart’s voyeuristic projection of his own fantasy – to murder Grace Kelly rather than marry her, is deepened by the audience’s voyeuristic of him.

This becomes Hitchcock’s way of enlisting everyone, audience and actors alike, in the vortex of universal guilt, the release valve that fantasy provides (Stewart’s desire to murder Kelly is both disguised and mitigated by his projection of that wish onto what he discovered Raymond Burr has done to his wife). Freud noted that sexual and/or fantasies of violence likely saved more marriages from divorce, and worse, than all the therapies in the world.

Notable in this film is Grace Kelly, as glamorous here as she was plain in Dial M for Murder. Despite the Grand Canyon difference in their ages, Stewart and Kelly share a strong chemistry, which make the volatility of the film even more intense, and nearly unbearable when she literally climbs into one of Stewart’s fantasies and nearly gets herself killed. Or is that, too, just a fantasy?

Vastly entertaining, with Raymond Burr in one of homely misfit character roles prior to the stardom Perry Mason brought to him on TV, Rear Window is not just one of Hitchcock’s grandest achievements, it is one of the all-time best films the studio era of Hollywood ever produced.

North by Northwest (1959)

5. North by Northwest (1959) finishes this round of Hitchcock films (we are showing NbN again to illuminate the growth and development from the director’s Saboteur. NbN is the far superior film, with extraordinary performances by Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint and James Mason, none of whom, as we might expect by now, are completely innocent or completely guilty.

As in Saboteur, the element of the “wrong man” is displayed here with customary Hitchcock flair, including widening the ambivalence of the screen to include Saint as one of those characters who continually switch sides, a neat take on the good/bad woman of so many films. Here, we are never sure which one she is; nor is Grant, and possibly Hitchcock himself.

The climactic scenes on Mt. Rushmore both recall and update the Statue of Liberty finale of Saboteur. Made and released after Vertigo and before Psycho, Hitchcock wanted a more commercially successful, “easier” film for audiences after the moderate earnings of the compelling, if hermetic Vertigo. See North by Northwest on the big screen as was intended, in all its theatrical splendor, including the melding of film and reality at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall, when it was still a movie house.

The climactic scenes on Mt. Rushmore both recall and update the Statue of Liberty finale of Saboteur. Made and released after Vertigo and before Psycho, Hitchcock wanted a more commercially successful, “easier” film for audiences after the moderate earnings of the compelling, if hermetic Vertigo. See North by Northwest on the big screen as was intended, in all its theatrical splendor, including the melding of film and reality at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall, when it was still a movie house.

Of the many films influenced by Hitchcock, to be sure, any film that advertises itself as being “Hitchcockian” signals how little, if anything, it has to do with the body of work of the Master of Suspense.

Until the next time…stay well, stay healthy, and go to the movies!

Read the first and second part of Marc Eliot’s Alfred Hitchcock Redux!

More content by Marc Eliot you might enjoy:

- Marc Eliot: Teaching The Art of Film for Students at the UFM Film School

- Marc Eliot’s Top 10 Classic Movies for Film Students to Watch

- Cine Foros UFM: Análisis cinematográficos de películas recomendadas por cineastas internacionales